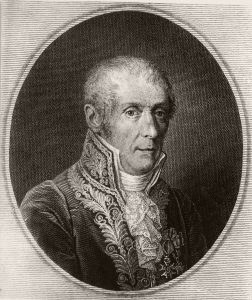

Volta, Alessandro

Volta was born in 1745. At first home-schooled, he then trained at a Jesuit School and at a seminary. his scientific activity began and, for a long time, developed outside of regular university institutional forums. In 1774 he was nominated regent for public schools in Como and in 1775 he became Experimental Physics professor at Como’s highschool.

It was in 1778 that he was offered the chair of Experimental Physics at the University of Pavia, where he remained for over forty years and of which he was elected President in 1785.

His extremely popular lessons were open to the public and held in the room now aptly named “Volta Room”. During his time, Volta greatly extended the instruments collection of the Physics Cabinet, even acquiring some apparatuses during his travels through Europe.

Volta was particularly successful in his electrostatic studies: his research on electroscopes, which he modified into electrometers, were fundamental. He also invented the condensing electroscope and the perpetual electrophorus – the first induction electrostatic machine.

Volta’s interest towards air breathability and what he called “flammable swamp air” caused him to invent a rather curious object, the “flammable air pistol”, and to develop a modification for eudiometers.

Most of Volta’s fame, however, is still linked to the invention of the battery pile. This fortunate invention was born of the dispute that Volta had with Galvani on animal electricity, which began in 1791. Galvani believed that the contractions of a frog’s legs, which he had observed during his experiments, were caused by an “electric nerve fluid”, typical to animals; Volta then conducted a great deal of research, at first replicating Galvani’s experiments and then producing his own, and came to the conclusion that the frog’s movements were simply caused by “metal” electricity, triggered by certain structures made of metals and humid conductors. In 1800 he made his column pile and his “pila a corona di tazze” (literally, crown of cups pile) public; in 1801 he presented his research at the Academy in Paris, in Napoleon’s presence, drawing immense success.

He died in 1827.